-

Recent Posts

- a Tribe or not a Tribe?

- Sovereign Structures and ‘Indigenous’ Land

- Exhibition Photos – Native States of America: Lakota Housing, Infrastructure & Economy

- Exhibition Opening 02.23.12

- Pine Ridge Builds

- Back on the rez

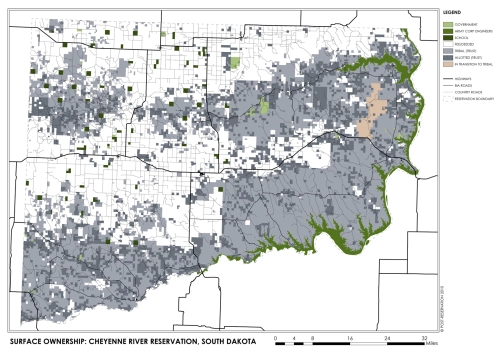

- Surface Ownership: Cheyenne River Reservation 2010

- Log Cabin, On The Tree

- WANTED: water

- From Hemp to Hulls – alternative constructions

-

Join 16 other subscribers

Categories

Top Clicks

- None

May 2024 M T W T F S S 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 Copyright

© Annie Coombs & Zoe Malliaros, Post-Reservation, 2010. Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this blog’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Annie Coombs & Zoe Malliaros, Post-Reservation with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

Category Archives: Infrastructure

Exhibition Photos – Native States of America: Lakota Housing, Infrastructure & Economy

Posted in Cheyenne River, Economy, Housing, Infrastructure, Log Cabin, Pine Ridge

Pine Ridge Builds

With each visit to Pine Ridge Reservation, we come across examples of innovative, sustainable building projects. In mid-August, we returned to visit Bryan Deans, who runs OLCERI (Oglala Lakota Cultural & Economic Revitalization Initiative) from his ranch in Slim Butte, on the southern side of the reservation. On the way, we stopped by a building project outside of Pine Ridge (the town). The team, led by Texas Natural Builders and Earth Tipi, is building a “pallet house,” which incorporates many of the materials and techniques we have seen in cob and straw bale buildings, but uses reclaimed shipping pallets as the material for the wall structure. The head of the building team, Dave, explained that this saves on the cost of raw materials, as the pallets are usually discarded and can be easily collected for little or no cost.

A gravel-filled drainage pit surrounds the home, and the walls are built upon several layers of earth filled bags, hammered flat. Once they create a frame, the walls will be filled with a light straw/clay infill and covered with 2” of cob and a layer of plaster finish, which Dave said should insulate to R20. The pitched roof will be insulated with cellulose (R30), and finished with pine shake shingles. Large windows look out from the front and back of the house, facing North and South, and deep overhangs will be built to shade the house and protect the walls from rain.

The kitchen and bath will receive water from the tribal water lines, and the bathroom will have a composting toilet. A solar panel will power basic electrical needs, and the owners have a 2000 watt generator as backup. For heat, the home will have a rocket mass heater built into the living room. A propane stove will be used for cooking, and an on demand propane heater will heat a small storage tank of water.The floor plan offers one kitchen / living space, 2 bedrooms, a bathroom and a 7’ loft space which is accessed by a staircase from the main living room. The home is being built for the Goings family, who were building a home for themselves until it was destroyed during last year’s rough winter. Seven people will share the space, four adults and three children.We asked the builders for a sense of cost, manpower and timing to build the structure and were told that the total cost would be around $10,000 and that a core group of 8 people could put it together in 6-8 weeks total. In conversations since, we learned that the total cost will probably be closer to $15,000 – still a far cry from $90,000which builds a “traditional” house for the Housing Authority.

The next day, we visited Henry Red Cloud’s land, between the towns of Pine Ridge and Oglala, where a team of volunteers were building a straw bale roundhouse. On the land, Henry Red Cloud has built a workshop for building and training in solar technologies – Lakota Solar Enterprises. The workshop houses volunteers and materials. Henry partners with the organization Trees, Water, People (based out of Colorado) and there were also many volunteers from RE-MEMBER. In addition to volunteers who live off reservation, we met a number of tribal members from other reservations. One woman was from Cheyenne River Reservation and is interested in building a home on her land next summer, while also inviting her friends and neighbors to take part and learn. Another man had traveled from Fort Hall reservation in Idaho (Shoshone tribe) and was planning to teach what he learned about solar heating and natural building when he went back.

This building was smaller than the pallet house, but was planned to be completed in two weeks. It was round, and it was planned to be divided into about three rooms – a main living space and two bedrooms. At the time of our visit, they had been working on it for three days and accomplished a lot. The structure was up, as well as the roof, and they were at the point when plaster is mixed (water, straw, sand and clay) and thrown against the straw bale walls.

Posted in Economy, Housing, Infrastructure, Photos, Pine Ridge

Surface Ownership: Cheyenne River Reservation 2010

The map below shows the “checkboard” condition of land ownership discussed in the previous post Whose Land? Land status and regulation.

“This “checkerboard” comes from a history of experimental and misguided land policies by the federal government. The General Allotment Act in 1887 designated 160 acre plots of land in trust to individual tribal members in the spirit of assimilation and “civilization” through farming. This land, if maintained, would automatically be turned to non-trust land after 25 years, slowly turning reservation trust land into non-trust land subject to property tax. This policy of “forced deeds” led to foreclosures and the sale of much of the original property on the reservations to non-Indians. Additionally, after the distribution of the 160 acre allotments, the “excess” or “surplus” land was sold off by the federal government to non-Indians – further reducing the size of tribal land. By 1919, 1,052,320 acres of the 2.8 million within the boundaries of reservation were “allotted” on Cheyenne River – a number that shrank to 503,483 acres by 2000.[1] In 2010, that number is 447,094. In 1934, Congress passed the Indian Reorganization Act, which prohibited “forced” deeds. Since then, one must request to convert their property to deeded land; otherwise it remains in trust.”

*Note: The map data shown was provided by the Bureau of Indian Affairs in 2010 and is subject to change.

Posted in Cheyenne River, Economy, Infrastructure

Log Cabin, On The Tree

The first homes built on the reservation by non-Indians were made by homesteaders, who introduced the log cabin typology to the region. Many of the log cabins we have seen were constructed in the early 20th century out of cottonwood logs. Between the logs, these cabins were insulated with local clay. In the 1970’s, the Housing Authority improved the insulation for some of these homes by installing new windows and adding a layer of stucco on the exterior of the homes. These log cabins typically have two rooms, a pitched roof, and no plumbing, and are built on grade. We have visited two of these cabins that have been abandoned and one that is lived in.

The occupied cabin we saw is outside the community of On the Tree, and had been abandoned for 6 years before the current residents moved there in September. This couple is living there with the permission of the rancher who owns the property, which is on fee land. They lease land for their horses to graze, but do not pay rent for their home. The cabin has two rooms, no running water, no electricity and a small propane tank for a gas stove. The residents currently can’t afford the cost of a water hook-up or to bring power lines to their home, but would like make that investment someday if they purchase the cabin. Currently, the house is lit by kerosene lamps, and reading is done with a camping headlamp. The small TV looked a little out of place, until we learned that it can be powered by the car battery just long enough to watch an occasional movie. Last winter, in order to heat the house using the wood burning stove, they went through 11 cords of wood, costing $100 per cord. They use two portable coolers (one small and one large) for any food storage, but must go daily to Eagle Butte, 20 minutes away, for ice and food. As for water, they have no cistern to periodically fill. Instead, they fill a 15 gallon jug at a hydrant 8 miles from their house and haul it back, twice a day. In the winter, when it is not uncommon to be snowed in and temperatures are predominately below freezing, this process can be quite difficult.

Despite its lack of infrastructure, Tess, the resident we spoke with, was very happy with her home. She has made it her own, and she enjoys her privacy in the vast open land. She said the wood burning stove provides excellent heat in the front room, which becomes the whole living space in the winter. All of the furniture is salvaged, but carefully picked and placed, and the house is cozy and comfortable. If she could change anything about the space, she would reinforce the foundation, upgrade the windows and doors, add more space for storage, get electricity – ideally through a turbine or solar panels, install a rainwater collection system, and build studio spaces for her and her husband to make their artwork.

The little technology she has access to she feels is vital. For example, she checks her email at the Dakota Book Club, where on a good day two of the three computers work. She did express frustration at the unreliability of the internet there, emphasizing that she refuses to give up on certain things functioning.

When we asked Tess if should would prefer to live elsewhere, she adamantly said no. She loves her home, and explained that her grandmother used to say “nothing is beyond repair”. She admits that sometimes living there is difficult and that surviving last winter was one of the most challenging things she has ever done. Ultimately though, she said that the biggest lesson she has learned is to surrender her expectations for many things. She sees this as a positive lesson, and embraces the challenges of their lifestyle as a worthwhile trade off for the independence and natural beauty she and her husband enjoy.

Posted in Cheyenne River, Housing, Infrastructure, Log Cabin, Photos

WANTED: water

One of the biggest issues currently facing Cheyenne River Reservation development is a water shortage, which is preventing the construction of new homes, and any new water hook-ups for existing homes.

The concept for a water supply and distribution system on the reservation was introduced at the infrastructural scale in the late 1960’s. By 1981, the tribe and Tri-County Water had installed an intake pump into the Cheyenne River, built a treatment plant south of Eagle Butte, and set up a main pipeline into Eagle Butte – the reservation’s largest town. Later, this main line was expanded east and west, and lines were placed north and south to pull in the outlying districts, communities and individual home sites, and to provide pasture taps (for a fee). In order to reach these outlying areas, Tri-County Water partnered with the USDA and Indian Health Services to expand and upgrade. Water storage tanks were put up in the 15 communities and 4 incorporated towns, ranging from 100,000 – 250,000 gallon capacity. Before 1981, people relied on deep (1000-2000 ft) artesian wells, which produced hard, salty water, or water delivery services.

The system was soon strained by a drought that affected the area from 1997 to 2008, an increase in housing demands, and high pasturing demand. Currently the pipelines are past capacity and Tri-County Water has put a hold on all new water lines and meters. An expensive, temporary fix moved the intake from the Cheyenne River to the Missouri River, and appropriations for 60-65 million dollars would be needed to make this fix permanent and to expand the main pipeline from the intake to Eagle Butte. This is a 4-5 year project, which does not account for expanding the lines out of Eagle Butte to smaller communities. Therefore, even though the drought ended 2 years ago, water flow is still impeded by the inadequate pipelines.

Originally, most rural homes built by the Housing Authority were equipped with cisterns, and received water through delivery. Over the years, many rural homes were added to the water supply system, eliminating the need for those cisterns. However, those who did not receive a meter before the moratorium must haul water to these cisterns in order to service their homes, as there are no delivery services left on this reservation. We recently had the opportunity to witness and assist in this process.

After looking in the water cistern and determining that water was needed, the process starts with securing a 300 gallon tank to the back of a pick-up truck and procuring a key and hose from the local store, off the reservation. Here, the water is purchased from neighboring Meade County. With tools in hand, we took five trips between a roadside hydrant and the home cistern, a mile long trip with some tricky truck maneuvering needed to align the tank’s spout with the cistern. In total, this process took half a day, and must be done approximately every two months by this family. As difficult as it can be during the summer, it is particularly taxing in the winter. The 1500 gallons of water supports the needs of a two-person home, where water is carefully conserved. Instead of using the indoor toilet, they opt to use an outhouse, as the water used for a toilet would require more frequent hauling. They have been requesting that Tri-County Water install a meter and line for ten years, but are still waiting.

Posted in Cheyenne River, Housing, Infrastructure, Photos

housing and its discontents…

We recently met with the Cheyenne River Housing Authority, the tribal office responsible for managing federal housing programs on the reservation. It was founded on this reservation in 1963, and is funded by the U.S. Department for Housing and Urban Development (HUD), which is often the scapegoat for the poor design and conditions of housing here. Until the 1980’s, the Housing Authority had little control over its designs, and the mandated HUD designs were of poor quality. While the Housing Authority has historically been the main provider of new housing on the reservation, there are other housing organizations that have built similar designs with similar construction materials and techniques. In general, these homes were not designed to withstand the harsh climate extremes. While it would be easy to blame the Housing Authority, HUD, and the other providers for substandard housing or maintenance, we have also seen that the politics of subsidized housing are not that simple.

Housing on the reservation often looks very similar, and while the Housing Authority has built the majority of the housing here, much of it has since been purchased outright and is thus no longer their maintenance responsibility. However, the general state of housing, characterized by vinyl or wood siding, broken windows (often single pane), shingled or metal roof (preferable), and single-story timber frame design, is makeshift and in varied states of deterioration. The biggest problem we’ve heard from people regarding their housing is that the windows and doors are not tightly sealed and that they are expensive and/or impossible to heat and cool. Houses tend to be drafty in the bitterly cold winters and hot in the summers (it was recently 109 degrees). While double-pane windows are required by building code on the east coast, where winters don’t get nearly as cold as they do in South Dakota, here we’ve see many houses with single-pane windows showing few upgrades/replacements. The Housing Authority assured us that they currently follow the International Building Code, however there is no Department of Buildings here. Any inspection of a property would be by internal inspectors. Other builders have told us that there is no enforced code.

Some of the damage and poor condition of houses can be attributed to the maintenance (or lack thereof) by the various housing agencies, but some is also due to mistreatment and neglect by tenants. Without a stake in one’s house, there is less incentive to upkeep or improve one’s space, especially when money is tight and homes are overcrowded. Furthermore, a large percentage of subsidized housing can create an economic culture of poverty, where there is no incentive to invest in one’s home and there are more incentives to be unemployed than employed. Here, Housing Authority rental housing is income based, so if you don’t work, you pay less or nothing at all. If you do work, your government commodities (similar to rations and/or food stamps) can be taken away and rent will increase with your salary (until hitting a certain cap). While many people do take pride in being independent, others choose to accept the handouts. For those who do work, rent remains a percentage of their income, so there is little incentive to earn more.

There is practically no private rental market on this reservation, so one must work with the Housing Authority or one of the other non-profits operating on the reservation to find a rental unit. This process is extremely slow, and the housing stock is relatively stagnant. The Housing Authority currently manages approximately 600 rental units on the reservation, while the waiting list for housing has over 400 people on it. The first person on the list for a one-bedroom house submitted their application in 1998. We imagine they may need more than a one bedroom, 12 years later.

The person we spoke with regarding the Housing Authority’s “modernization program” informed us that the oldest HUD designed houses from the 1960’s can have exterior walls constructed out of 2 x 4’s. This doesn’t leave much room for insulation. The “modernization” department is responsible for construction updates due to damages and normal wear and tear, but renovations can also be needed in the case of “tenant abuse.” This is when the tenant so badly abuses the property that it requires renovation. The way “modernization” works is that the Housing Authority periodically inspects their units and reports the “worst of the worst” conditions. Those properties get put on a list for modernization, but a tenant cannot request their home to be modernized. We’re hoping to see examples of houses before and after this modernization process next week, but were told that repairs can range from kitchen/bathroom updates to full interior renovations.

With regard to ownership, we met with a woman at the Housing Authority who is responsible for home ownership educational programs and funding. She spoke with us about their relationship to the reservation, the housing types they provide, the setbacks because of water shortage, and the Housing Authority’s vision for the future of housing on the reservation. She told us about several mortgage packages, educational programs and advisement that provide options and support for tribal members who are interested in purchasing a home. However, it is currently difficult to build new housing because of a water shortage, so they can only advise people on purchasing already built homes or trailers. In the past, the Housing Authority did have a rent-to-own program, but this is no longer available.

We were really excited to meet with the Housing Authority and hear their side of the story. It appears that the biggest setback to creating new housing at the moment is the water shortage. In essence, the existing water pipes and reservoir for the reservation cannot accommodate the demand, and Tri-County Water, the sole provider for the reservation, has put a hold on new installations and water meters. A new water reservoir has been created but the funding hasn’t come in to lay new pipes and finish the pumping station. This could take a couple of years to be completed. Until then, there will be no new traditional water lines and thus, no new housing unless you pay for an alternative to the county water system. At the moment, the Housing Authority does not plan to explore alternatives like digging wells or developing rainwater collection systems, as this is too costly for on their budget. Thus, they will not build until the water shortage is solved.

There have been roads and infrastructure laid for a new housing development near the main town of Eagle Butte, called Badger Park, which is currently on hold due to the water shortage. The plans for this community do include a number of new ideas and experiments, including alternative building techniques and updated designs by an architecture firm in Pierre. These houses would be built in modular pieces by the Housing Authority on a lot in Eagle Butte, and then moved to their sites to be assembled and hooked up. We are planning to meet with this firm and other Housing Authority officials to discuss the details of these designs.

We also learned of an exciting project in the residential community of Cherry Creek which fell under the Housing Authority’s modernization program for rental units. Six houses have to be moved to a new location in town because they are in a flood plain. The Housing Authority received government funding and will experiment using geothermal heating in these homes. This could drastically reduce the cost of heating in the winter and provide an example for implementation of energy-conscious building techniques.

While we felt like our initial meeting at the Housing Authority provided a lot of new information about their scope of management and the housing stock, we still have more questions about specific building techniques and historic data. We want access to the GIS maps that show land ownership, roads, utilities, geology and housing location/vintage, but are having trouble getting this information. We hope this will not be necessary, but an attorney for the Department of the Interior in Washington DC has advised us that we may have to file a Freedom of Information Act request if we keep getting blocked from accessing information that is public. We have now met with the BIA, Housing Authority, and Games, Fish and Parks, all of whom have been incredibly generous with their time and discussions of their work, but reluctant to share what we feel is important spatial information. Each organization has pointed us towards another to get this information, when they all have it in one form or another.

Posted in Cheyenne River, Economy, Housing, Infrastructure, Photos

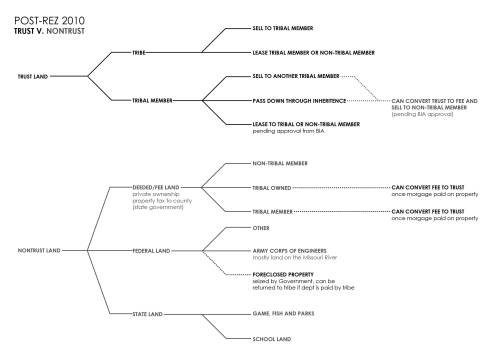

Whose land? Land status and regulation

Laws regarding land use, ownership and taxation influence everything that is built on reservation land. There are several categories and subcategories of land, each with their own laws regarding taxation, land value, control, and economic potential. The main categories of land status are “Trust” and “non-Trust” (also called Deeded or Fee). The concept of “trust” goes back to the creation of reservations by the Federal Government, as an attempt to protect tribes and their new, enclosed land. However, the trust relationship has played out in a way that has led to a checkerboard pattern of land control by the tribe, and complications in the economics of home ownership by individual tribal members.

History:

This “checkerboard” comes from a history of experimental and misguided land policies by the federal government. The General Allotment Act in 1887 designated 160 acre plots of land in trust to individual tribal members in the spirit of assimilation and “civilization” through farming. This land, if maintained, would automatically be turned to non-trust land after 25 years, slowly turning reservation trust land into non-trust land subject to property tax. This policy of “forced deeds” led to foreclosures and the sale of much of the original property on the reservations to non-Indians. Additionally, after the distribution of the 160 acre allotments, the “excess” or “surplus” land was sold off by the federal government to non-Indians – further reducing the size of tribal land. By 1919, 1,052,320 acres of the 2.8 million within the boundaries of reservation were “allotted” on Cheyenne River – a number that shrank to 503,483 acres by 2000.[1] In 2010, that number is 447,094. In 1934, Congress passed the Indian Reorganization Act, which prohibited “forced” deeds. Since then, one must request to convert their property to deeded land; otherwise it remains in trust.

Trust (allotted to tribal member or owned by tribe):

Only the tribe (as a political body) and individual tribal members can own trust land. This land cannot be sold or transferred to a non-Indian. The benefits of trust land are that no property taxes are paid on it, and it can be passed down within the family. Land passed down through family can only go to tribal members. In the case that it is not passed on, it will be returned to the tribe. Trust land can be traded for other tracts, or can be sold within the tribe. Ownership can be beneficial, title or both – affecting whether income is received from leasing of the land, and how the land is transferred after death. Some tracts of land are 1 to 1 individual ownership, but most land is considered to be “undivided interest land,” meaning that it is in trust to several family members. In this case, an individual owns a percentage of the land, but not a segment. Since the land is in trust by the federal government to the tribe, the land cannot be sold to non-Indians, and the BIA has the power to approve or reject transactions.

Nontrust (also known as Fee or Deeded):

The reservation borders include a sizable amount of land that is not in trust, and has very different regulations that govern it. This land, called “fee” or “deeded” land, is owned in full by anyone, Indian or non-Indian, and is subject to property tax. It can be sold or leased at will. It was only recently that the tribe gained 51% control of the land within the reservation, after the purchase of 24,000 acres of deeded land. It is still considered deeded until the debt is paid off, and then can be converted to trust land. Before this transaction, the tribe didn’t hold the majority interest on its own reservation.

Indian Country:

Indian Country is trust and nontrust land that is within the boundaries of the reservation and any territory outside the reservation that is under the jurisdiction of the tribe. Private property on fee land in Indian Country is subject to US and county taxes. However, these properties are under mixed jurisdiction between the tribe and federal government. For example, if a non-major crime is committed between Indians in Indian Country, the tribe has jurisdiction. However, if an Indian commits a crime against a non-Indian or vice versa, it is considered a federal crime, and the FBI has jurisdiction – not the state. All major crimes on the reservation, such as murder and rape, are under FBI jurisdiction.

Conversion Programs:

Individuals who own trust land can apply to have their land converted to fee-simple land, a practice that is usually only done if a tribal member wants to sell their land to a non-Indian, as it subjects the land to taxation. In this case, the land ceases to be considered “reservation” land and is no longer in trust for the tribe. Another process is the fee-to-trust program, in which a tribal member can apply to have their fee land converted to trust land. This process can only be started if all buildings on the property are paid in full.

City/Town Incorporations:

Four towns within the reservation, Dupree, Eagle Butte, Isabel and Timber Lake, have large sections that are incorporated by the state. Being incorporated by the state means that the land is deeded and is most likely not owned by the tribe. For example, in Eagle Butte the two main gas stations are in the incorporated section of town; the tribe does not own them. In fact, there are two Eagle Buttes – Cheyenne Eagle Butte on trust land and Downtown Eagle Butte on fee land. On tribal land there is no zoning. To create a commercial site, each individual business venture must go through an approval process by the Tribal Council and BIA, a process that we have been told is tedious and long. This is particularly problematic for the 15 residential cluster communities like Bridger, Cherry Creek, Iron Lightning and White Horse that are on reservation trust lands but have no precedent or encouragement for commercial activity.

Surface/Minerals:

After studying a map in the realty office of the BIA, we noticed that it was labeled “surface map,” and learned that surface and mineral rights are independently controlled and can have different trust statuses. For example, in the case that surface land was allotted to an individual and in trust, the minerals below could be fee land owned by another individual. Legally, mineral rights trump surface rights, so if the owner of the mineral rights wants to access their minerals, they can penetrate the surface land. Because of this, the tribe’s current policy is to always keep mineral rights in trust when selling any fee land.

Housing Process:

Tribal members can apply for home sites on tribal trust land, which would then be leased indefinitely or traded for individual ownership. Site selection involves the study of a GIS map showing which land tracts are available. Typically, an application is for a five-acre home site. The leases are usually for 25 years, and are generally renewable for another 25 years. After tribal approval, the individual will be responsible for developing the property within 2 years, and will be responsible for acquiring housing on the site, and applying for utilities from the independent companies that sell electricity, propane and water. Tri-County Water charges between $600 and $1000 to install a water meter, though some programs (eg. Indian Health Services) may assist with the costs. However, there have been no new home sites selected in the past three years, due to a current hold on new water meters by Tri-County Water. Pipes laid in the 1970s were too small for current demand, and due to maxed out pipes and pumping station, new water meters will not be installed until a new intake, pump and treatment plant is completed in Armstrong County. This could be several years, depending on funding and climate conditions. Until then, only sites with previously installed systems are selected (and these are rare), unless a cistern system is used to laboriously haul and hold water, or a more robust system of rainwater collection is put into place.

Range Units:

Much of the undeveloped land within the reservation boundaries is leased to ranchers though a system of Range Units (RU’s). Individual tribal members can apply to the tribe for 5 year leases of range units, and do not pay taxes on the land. Lease money is paid to the tribe, and the amount is calculated according to the number of animal “units” that can be run. In order to lease a RU, an individual must run at least half of his or her own animals on the property– either all together throughout the year, or half a year at a time. Generally, cattle graze the land, but horses also count for this percentage. The price of leasing land from the tribe is significantly less compared to leasing land from individuals with allotted plots of land – approximately $7/acre compared to approximately $17/acre. Still, these Range Units provide a substantial source of income to individuals who are lucky enough to have them. Range Units are difficult to come by and currently there are none available. The application process includes a non-refundable $100 fee and the selection process is not based on a list or any clear criteria, but rather appears to be a political decision made by the tribe.

[1] Indian Land Tenure Foundation, http://www.indianlandtenure.org/iltfallotment/introduction/introI.htm

Posted in Cheyenne River, Economy, Housing, Infrastructure

Landscapes from the road, Pow-Wow, etc.

Posted in Cheyenne River, Housing, Infrastructure, Log Cabin, Photos, Pine Ridge

Infrastructure We’ve Seen

Many things we take for granted back at home in New York City are simply unavailable or slow to get around here. If you’ve tried to call us on our Alltel cell phone, you probably got cut off at some point. Alltel is the only cell phone carrier who has invested in putting towers on the Cheyenne River and Pine Ridge reservations. We are grateful for the signal this has provided our phones, but it is still patchy. Your best bet for a strong signal is a hilltop, taking a road on the perimeter of the reservation or getting close to a cell phone tower, which aren’t always near towns. We spoke with a native woman today who took her Alltel phone to New York City, only to discover it didn’t work on the east coast because Alltel doesn’t have roaming agreements with carriers there. Our provider, AT&T does provide roaming service around the country, but has no compatible towers in this area – we must be in the 1% of the country they can’t guarantee service.

Internet is another story. Getting a fast connection requires the installation of a costly satellite dish. There are no cable lines laid so DSL and wireless are not options. There are no “internet cafes” on the entire 4,266.987 sq mi of the Cheyenne River Reservation, which is comparable to the size of Connecticut. If you want access to the internet, you can visit the Dupree YMCA in the center of the reservation. We also heard that there are two computers at the sole small public library on the reservation, but we have yet to confirm they have internet.

Yesterday in Dupree we saw first hand some of the destruction caused by 23 tornados, which simultaneously hit the town on June 16th, 2010. Though much debris has been cleaned up, evidence of the damage is clear on the houses and farm structures. Many of the houses are missing parts of their roofs, replaced by plywood, and a lot of windows are boarded up. Given that it has been extremely rainy for the past few months, it is clear that these patches are not sufficient. A woman, who works at the YMCA, ironically confirmed this during a rainstorm yesterday. She was concerned about her house, which had been damaged by the tornadoes, and had unfinished repairs by the Housing Authority maintenance crew. She described long waits for service, and mentioned soft parts of the roof and ceiling in several areas of her family’s home. She was not expecting any follow up service, despite the fact that she feels the job is not finished, and was worried about the effects of yesterday’s rain on the house. We are told that the Housing Authority receives money in lump sums. They spread it as thin as they can, to help out as many people as possible, until they run out of money. Then they wait for more. This explains why so many of the windows in Dupree are boarded up. When the next sum of money comes in, hopefully the Housing Authority will install new windows. There is no telling when that will occur.

Posted in Cheyenne River, Housing, Infrastructure, Photos